- Home

- Hackshaw, Peter

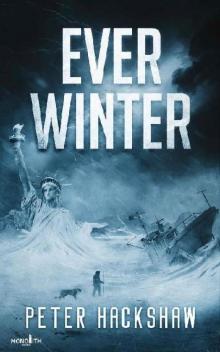

Ever Winter

Ever Winter Read online

Ever Winter

Peter Hackshaw

For Laura, Arthur, Violet and Rose.

Contents

Part I

1. Meat

2. Whiskers

3. The Crudest Refinery

4. A Relic

5. A Duesenberg

6. Skills

7. Road to Ruin

8. A Bedtime Story

9. Salvagers

10. Grotto

11. The End of the Beginning

12. Moonbird

13. Chore-up

14. Hello, Darkness, My Old Friend

15. Therapy?

16. How to be Human

17. Under a Canopy of Stars

18. Some Distance to Olympian

19. Beast Mode

20. Lessons in Absolute Violence

21. Canary, Caged

22. Changeling

23. Time Travelers

24. Husk

Part II

25. Pickings

26. Underbelly of a Dead Dog

27. Ungodly

28. A Ripped Black Flag

29. The Girl Who Would be Queen

30. The Inhuman Condition

31. The Rambling Man

32. Dream

33. To Catch a Royal Snitch

34. Tattoos

35. Dead Dogs

36. King of Hearts

37. Fury Delivers Landside

38. Shaming Shadows

39. Man, Made Flesh

40. Falling Dominoes

41. A Fine Garment Made of Skin

42. The Willow and the Wisp

Acknowledgments

Part One

One

Meat

Henry had only ever laid eyes upon one man who wasn’t of his kin, and he’d not been long dead when they found him.

“Meat is meat,” Father said, then went about the fellow with a whalebone in the normal fashion, not hurrying the task, but casting a watchful gaze about them as he cut.

The snow had not yet covered the man’s tracks and Henry could tell he’d not been killed where he lay. If he had, another human or beast would’ve done the same as them and taken the primal cuts.

Father held the man’s clothing up, revealing a pale, sunken chest. Its skin stretched tight over a ribcage that no longer heaved with the rhythm of the lungs.

“This is where they stuck him,” Father said, gesturing toward a slit of a wound between two of the man’s ribs. It reminded Henry of an eye, although he didn’t say so. The late afternoon sun had started its slow descent and a gust of wind snapped at them, whipping Henry’s dull, mouse-colored hair across his face. He gathered it in a gloved hand, tucked it into his hood and pulled the hood as far as he could over his forehead. A scarf covered much of Henry’s face and trapped the warmth of his breath within.

“Must’ve fled and thought he’d got away, but the blood escaped him too quick. Can’t bolt from the cold, either.” Father held the layers of clothing as if he were counting them. “Weren’t dressed too well for it… wearing man-mades...”

Henry nodded, still transfixed by the neat hole that no longer bled. The dead man’s meager garments were a stark contrast to their own: Father wore the pelt of a Big White with the head still attached, which made it look as if Father’s skull was held between its jaws, while Henry’s coat was a mélange of furs – a tapestry of arctic fox and the wolverine, the muskox and the sea lion.

Father continued to hack off what pieces he could, poking his tongue out as he always did when concentrating.

“Don’t know what he was doing this far out o’ Lantic.” Their homeland had once been a vast ocean, before the Ever Winter. It stretched for hundreds and hundreds of leagues in every direction. It was one icescape, one color, and it was all that Henry had known.

Still saying nothing, Henry finally moved his gaze from the man’s fatal wound as Father pulled innards outward and bagged them in a sealskin. Bile rose in his throat, and he thought for a moment that he might throw up in front of Father. He loosened his face-scarf and took a deep breath of the crisp air.

“Guts are bad eating, but we’ll use ‘em for bait,” Father said.

Henry looked away, only to be drawn this time to the man’s face. It was a death-mask, frostbitten in places and set in a final expression of accusation. Henry couldn’t help feeling guilty under the corpse’s silent scrutiny. He blinked, letting the dead man win their staring game, then scanned the distance for any sign of movement.

“Why don’t we drag him, Father? I could fetch the sled.”

Henry wanted to get home. He daren’t admit it then, but he was worried. He’d always wanted to meet others, but this wasn’t how he’d ever pictured it.

Father cast him a withering look. The cold formed a mist that appeared to take his words away as he spoke them.

“This dead ‘un might have companions. My guess is, they’ll be looking to finish the job. They’ll want proof of a kill... or the man-meat. Likely both.” He pointed the whalebone at the corpse, then cut deep into the leg around the calf muscle, making a large diamond in the flesh, which he stripped and bagged with the innards. Henry knew Father would be cursing that he didn’t have his saw, which they’d left beside the ice-hole they’d fished the past month, for when it froze anew.

“Take half a day to get back here with the sled,” he continued. “Might take ‘em less to find him. If we drag him between us without the sled, his deadweight will be a burden. We’d be slow and asking for trouble with the Big Whites.”

Father paused for a second, wiped gems of ice from his beard, then carried on cutting. “We take what we can and we move swiftly on, let the snow cover our tracks, take a long route so it does the job and lets none fathom our desty.”

Father gave Henry a pointed glance and Henry realized he was supposed to be helping.

Taking the hint, he checked the man’s boots, only to find them useless; old, man-made and long worn. He took the laces, then wrestled the dead man’s jacket from him, trying to ignore the corpse’s head as it bobbed in resistance to their vulgar robbery. He unzipped the fleece that formed the second layer, while Father took what meat he could.

Henry met the corpse’s gaze once more. He pitied the dead man and pondered what kind of person he’d been. Had he deserved his death? It mattered none, but he fancied they might have talked had they found him sooner. They might have learned of the other remnants out there. People.

Henry bagged the garments they wanted to keep. The dead man had no sack nor satchel upon him; no food, or spear. He had no means of lasting a single night exposed.

In a hidden trouser pocket, Henry found a slim knife that Father called Anteek, which meant it was very old. It had been sharpened and oiled and Henry tried it against the dead man’s lower leg. He found it good for stabbing the frozen matter, but not sufficient to hack off a limb. Resigned to the fact they could only strip flesh from the man in crude squares and diamonds, they turned the corpse face down in the snow to get to the easier rump cuts. All the while, the sun set defiantly in a blaze of pinks and oranges that they both ignored.

-

The trek home was the nearest to silence that Henry could remember. There was a tautness in the air as they tramped through the powder snow, Father deep in thought, clutching the sealskin tightly to his chest.

After some time, Henry realized they’d picked up the pace, though he wasn’t sure which of them was responsible for the swiftness in their strides. They soon grew weary in the blizzard that met them after the day’s light had been extinguished, an hour into their exaggerated route back to their homestead.

“Don’t scare the girls none, Henry… nor Martin either. No talk of him being stuck. We say the cold got him, which it

likely did in the end,” said Father. Home was finally in sight; a distant smudge on the otherwise flat and sterile icescape.

“Ain’t never seen a man other than you, Pa,” Henry uttered. “That dead ‘un was taller than me, but he wasn’t nearly as big as you.”

He wanted to say more, but was unsure what else to say. So, he kept quiet and concentrated on the warmth of the blubber lamp, which would be burning low in the igloo to keep the boy-bairn warm. He imagined there might even be a broth awaiting them, which was a rare treat on account of the baby and the fact that his mother needed her strength for the milk. Henry smiled to himself at the thought of seeing his siblings.

The wire encircled the homestead and protected them from Big Whites and other predators, who would become ensnared in it should they try to cross. It was a tangled ring of items collected over the years; things found in the ice, mostly. Frayed and broken things that hinted of the old world: scraps of metal and plastic, and bones from the animals they’d eliminated, which rattled collectively in the wind. They’d killed a few things that had gotten caught in the wire over the years and found some already dead from the struggle. In a way, the wire was both forcefield and monument, and in rare times of a still, peaceful wind, it became an alarm bell.

Father threw the sealskin over the wire then carefully wrangled through the jagged web. Henry followed, snagging himself on it momentarily until he unhooked himself. Father shook his head as he waited.

Night had fallen. The starry sky lit the icescape below it and the igloo, a perfect disc shape, mimicked the full moon in its elevation.

They passed the ice-hole they’d cut to expose the seawater below and allow them to reach the fish underneath, then they reached the narrow entrance of their home.

-

It was a strange taste; man-meat. It was indeed a prize, although raw. They stored most of it, and as they ate the rest, Henry wondered if he could ever bring himself to eat the meat of his kin. He watched them as they all chewed in silence: Mother and Father; his sisters Mary, Hilde and Iris; his brother Martin; and the boy-bairn who was sleeping in Mother’s arms. Henry wondered if they all shared the same thought at that moment.

Father broke the silence and said that providing sickness had not taken a body, they should eat, even if it were one of them. Iris, the youngest of the girls, couldn’t contain her laughter, but the others kept serious faces.

“It’s just meat. ‘Tis food,” he continued. “You can have mine when the time comes, but not for a few years yet!”

They all laughed then, although Martin seemed bewildered by it all and looked like the littlest thing would make him cry. Martin always had a worried look upon his face. They finished their meal in silence.

A shard of reflective glass hung from a coil of flex in the center of the igloo. It had once been part of a gilded mirror that had been intentionally shattered and the pieces shared amongst families in the time of the Great-Greats. Henry caught glimpses of his siblings in the glass as it turned. Mary, Hilde and Martin all resembled Mother, with their fair hair and blue eyes and the same identical nose that tipped up slightly at the end. Mother’s ancestors had come from a place far to the north, but the name of the place had been forgotten over time, though they still knew some of the words the people from that land had spoken.

Henry and Iris had darker hair; mousy in color, almost brown. They shared a constellation of freckles that trailed across their noses, and had fuller cheeks with dimples. Although he was closest in age to Mary, Henry felt more of a connection to his youngest sister, who followed him around whenever he was home. He supposed they took after Father, but it was hard to envisage. Father had long silvery hair and his face had been cloaked with a thick beard for as long as Henry could remember. The skin on Henry’s face was smooth, like his sisters’, although he’d gotten hair in other places which had seemed to happen overnight. Father’s eyes were more green than blue (like Henry’s) and he was very tall, with a heavy frame, whereas Henry was skinny beneath the layers that cloaked him. He doubted he’d ever be the size of Father, but even Father had been a boy once.

-

Iris grew tired and laid her head on Henry’s lap. Henry entwined a curl of her hair in between his fingers and watched as Mary and Hilde played backgammon on the fine board their mother had once hewn from the bones of a beast long-frozen in the ice. Hilde lost her tokens as she always did and went to bed in a sulk, which was her way.

Unaffected by her sister’s actions, Mary carefully unwrapped the plastic bag which protected the family’s only book and started to read from where she’d left off the night before. It was a very old, frightening story of a demon that dressed as a clown and murdered children in a world that no longer existed.

Henry had read the book himself more than twenty times. He found it terrifying in places, but lots of the chapters confused him. There were too many words that his family did not know the true meaning of and too many things that were completely alien to him. What was television? What was a storm drain, or a pig, or a balloon, or a cola? What was a Batman? What was a 1958 Red Plymouth Fury?

The words in the book described what a clown was, but that wasn’t enough for Henry to picture one clearly in his mind, or comprehend what its purpose was, other than someone (or something) appearing as something else.

Martin and the bairn clung to Mother, who looked exhausted and ready to let sleep take her. She kissed the bairn on the forehead and smiled at Martin, who was resisting going to sleep himself. His eyelids were heavy and he blinked defiantly, trying to stay awake and repel the inevitable.

Meanwhile, Father sorted through the belongings they’d taken from the man who’d become their meal, discovering a small wind-up torch in another secret pocket which layers had cushioned and concealed when they had frisked the man.

Father pointed at the torch triumphantly in the silence and Henry nodded, as pleased with the find as Father was, but unable to move through fear of stirring his sister or disturbing the others. The torch shone brighter in the igloo than the blubber lamp and the fact that it needed no oil was in itself miraculous. Father continued to play with the torch, drawing ribbons and bows with its light, but careful not to shine it near his family as they slept beneath furs and timeworn blankets. Just as the wire circled the igloo, the family formed a circle within it. They were the hours of the clock and the mirrored glass was the center-point of the dial.

After finally carrying Iris to her bedding, Henry wandered outside beneath the brilliant stars that dotted the nocturnal canvas above him, providing their own light. He gazed out toward the wire and the infinite whiteout beyond it. Henry tried to imagine a place where people lived amongst others; tens of families, maybe hundreds, with children his age. He thought of new conversations and the sounds of new voices. He tried to imagine faces that were unlike those of his family, and pictured unnamed girls that were not his sisters. But the visions in his mind all morphed into one or all of his siblings.

Henry stared at the constellation he loved the most; Canis Minor, ‘The Little Dog’. It wasn’t the brightest, or the most spectacular, and that was why it was special to Henry. He had chosen it as his favorite amongst all others.

After some time lost in a tangle of his own thoughts, Henry went back inside and cocooned himself in his sleeping bag, zipping it up to his neck. He closed his eyes, but his mind was haunted by the face of the man his family had eaten.

Sensing that his brother was awake, Martin whispered from where he lay beside him, “What did the man look like, Henry?” Martin’s voice was a higher pitch than Henry’s, which emphasized his youth. Henry lay with his back to Martin in the darkness, but he could imagine the exact earnest expression that his brother likely wore.

Henry let the question sink in. He tried not to, but it was impossible. He saw the man’s patchy dark beard and sunken cheeks and hollow eyes. He saw cracked hands and black fingernails and crooked teeth in a wide-open mouth, with a tongue that his father had removed for

the feast.

Henry tried to think of a clever answer to keep his brother quiet, which was usually no task at all, but he had nothing to offer and so Martin asked again, thinking Henry had not heard him the first time.

“He was just a man, Martin,” Henry replied casually, as if it were entirely normal to see a stranger, something that happened every day on Lantic.

Martin wasn’t satisfied. He pressed him further, until Henry finally gave up and turned to face his brother.

“He looked about the same age as Father, but he wasn’t as big.”

Martin seemed pleased with the morsel of information and gave up for the evening. Henry turned to face the igloo wall once more and wondered how old his father truly was. He didn’t know how old he was himself, although it was somewhere between ten an’ three and ten an’ six, according to his mother. Mary was one younger than him, Hilde one younger than her, Iris was nine or ten and Martin was closer to seven.

That night, Henry dreamed that the man they’d eaten had Father’s face. Over and over his mind replayed the cutting of the man’s flesh, and each time his father was pulling all kinds of expressions, trying to communicate, although no sound came from him. He knew in the dream that Father was still alive, even as he was cutting and bagging him. Father could not protest, as his tongue was in Henry’s pocket.

Ever Winter

Ever Winter